- Bow Valley Insider

- Posts

- Skiers Trace a World-First Line on One of Banff’s Most Photographed Peaks, Above Moraine Lake

Skiers Trace a World-First Line on One of Banff’s Most Photographed Peaks, Above Moraine Lake

Christina Lustenberger, Brette Harrington, and Guillaume Pierrel complete the first ski descent of Mount Deltaform’s North Glacier

For anyone who has stood at Moraine Lake or hiked into Larch Valley, the Valley of the Ten Peaks is instantly recognizable. One of those summits, Mount Deltaform, dominates the western end of the skyline. Earlier this month, it also became the site of a world first, the first ski descent of its North Glacier, completed by Brette Harrington, Christina Lustenberger, and Guillaume Pierrel.

The descent, carried out between January 17 and 19, unfolded on a steep, broken face of hanging ice and snow high above one of Banff National Park’s most visited landscapes. According to The North Face, which sponsors Harrington and Lustenberger, the three alpinists began their approach from the Moraine Lake trailhead, hauling skis, ropes, tents, and food 17 kilometres on toboggans in midwinter temperatures that dipped below minus 18 degrees Celsius.

Basecamp at the deep in the Valley of the Ten Peaks (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

“We departed the Moraine Lake trailhead at 7 a.m. on January 17th,” Lustenberger wrote. “Hauling our gear in toboggans, we covered 17 kilometers to reach the base of Mount Deltaform, setting our tent up deep in the Valley of the Ten Peaks, below our objective.”

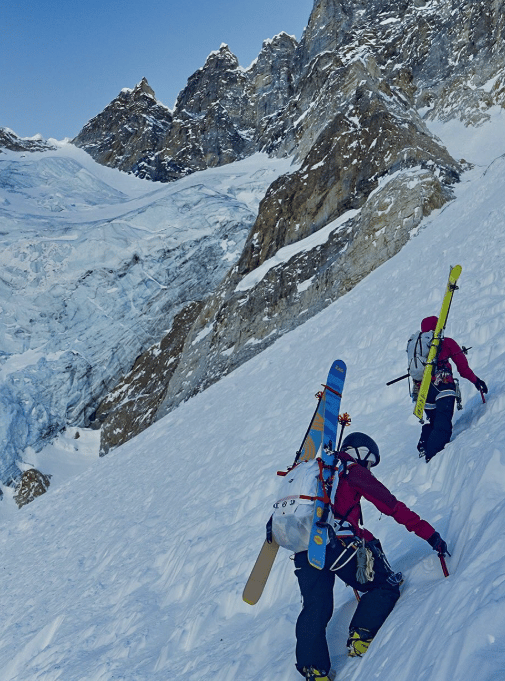

From that camp, the team began their climb the following morning, ascending exposed ramps and a narrow couloir before rappelling onto a hanging glacier, a steep mass of ice clinging to the mountainside rather than flowing all the way into the valley below. They then continued upward through a maze of towering, unstable blocks of fractured ice, constantly exposed to the threat of icefall.

Climbing the steep couloir (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

After reaching the summit, the descent that followed was not a continuous ski run but a complex sequence of steep turns, stops, and rope work, as the team skied short sections, then built anchors and rappelled over cliffs to access the next patch of snow.

Nearing the top of the couloir (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

After climbing onto the hanging glacier and reaching the top, Lustenberger wrote, the team “transitioned and skied to the edge of the hanging serac, making two rappels to access another hanging snowfield. Two more rappels delivered us onto the lower portion of the route, where we finally skied all the way down and back to camp.”

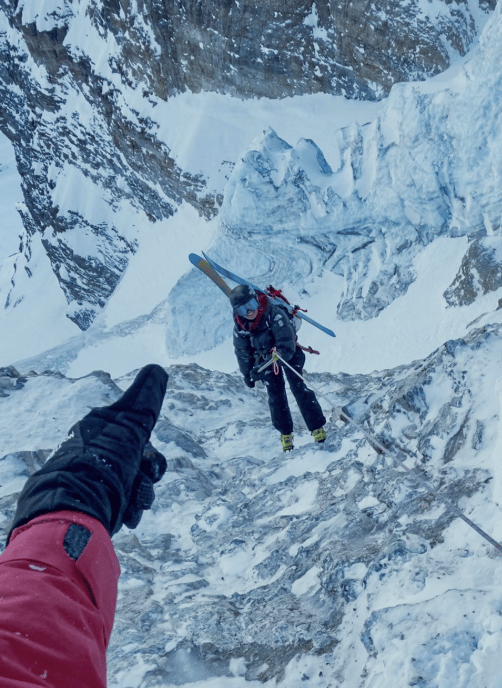

Rappelling next to huge ice seracs (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

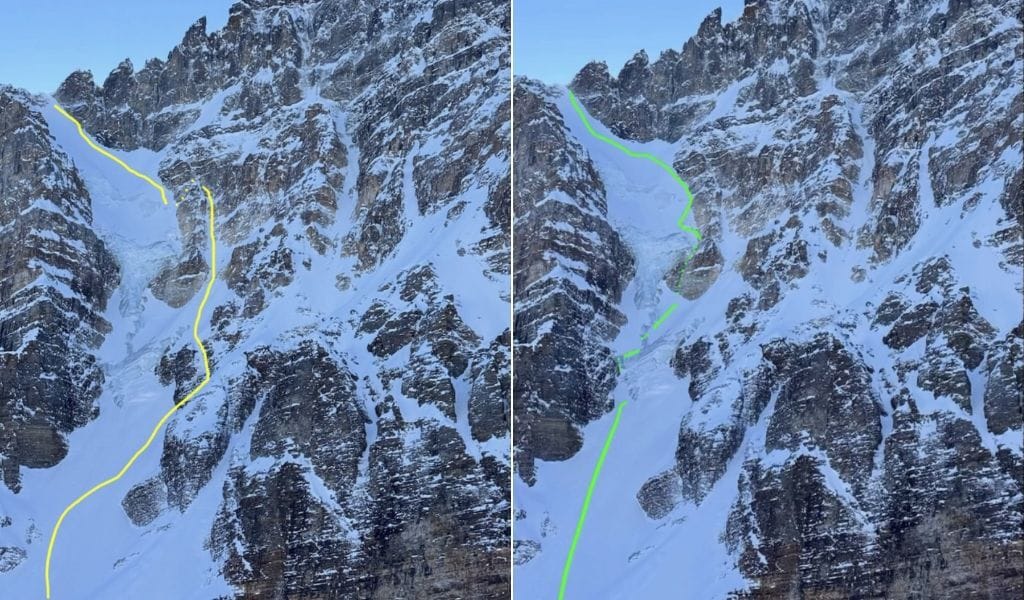

Outside magazine, which reported on the expedition, described the line as a patchwork of narrow couloirs, exposed snowfields, and four separate cliff bands, all threatened by falling ice from the glaciers above. The slope angles reached close to 50 degrees, far steeper than anything encountered at a ski resort, and the team chose not to climb their intended ski line on the way up because of the constant risk of icefall.

“There was always the reality of falling ice,” Pierrel told Outside. “When you get up close to it, you can see these pieces, like two or three meters, just hanging and ready to fall.”

Rappelling a cliff band (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

That decision meant committing to the descent without having closely inspected the snow and ice conditions beneath their skis, a level of uncertainty that adds another layer of risk in already extreme terrain. For Oakley Werenka, a Bow Valley mountaineer who has climbed Deltaform in summer, the idea of skiing it hardly seems plausible at all. “My first intended thought is that it doesn’t look like a ski line,” he said.

Left: Ascent line. Right: Descent line. (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

To negotiate the route, the skiers repeatedly edged to the brink of vertical drops to place ice screws and build anchors, then clipped in and rappelled, sometimes into empty space, before skiing again.

Building an ice anchor (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

“Skiing up to the edge of a void is always pretty intense,” Lustenberger told Outside. “You’re not skiing up to this established anchor point where people have done it before. We’re figuring it out.”

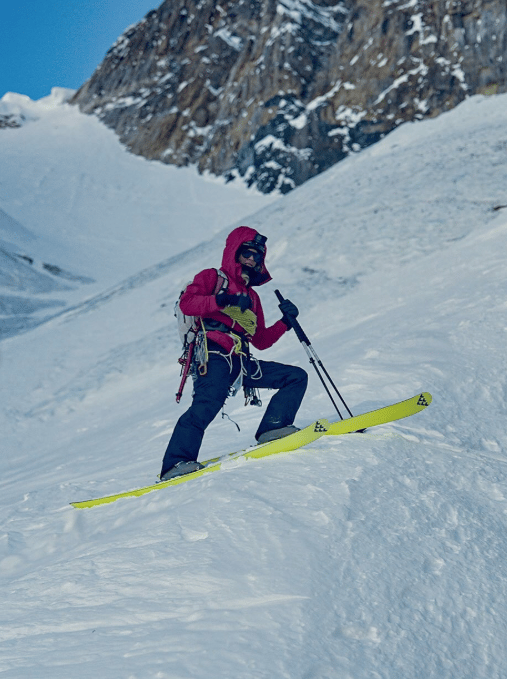

Christina Lustenberger descending the North Glacier of Deltaform (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

While the achievement drew international attention, the three athletes also have strong ties to the Canadian Rockies and the Bow Valley. Harrington, an American climber and skier, has spent years training and climbing in the region and is widely known as the partner of the late Marc-André Leclerc, whose solo ascents were chronicled in the 2021 documentary The Alpinist. Lustenberger, a Canadian steep-skiing pioneer, and Pierrel, a French alpinist, were recently featured together in the film Robson, which premiered at the 2025 Banff Film Festival and documented their historic first descent of Mount Robson’s South Face.

Ascending one of the cliff bands (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

That project further cemented their reputations as two of the world’s leading ski mountaineers, capable of linking technical climbing and skiing on faces long considered beyond the reach of skis. Deltaform, though less famous than Robson, occupies a special place in Canadian mountaineering. Rising to more than 11,000 feet, it is the tallest peak in the Valley of the Ten Peaks and one of the more demanding objectives among the Rockies’ so-called “11,000ers,” known for shattered limestone, complex route-finding, and long, exposed ridges even in summer.

In winter, its north-facing glaciers hang in shadow above Moraine Lake, shedding falling ice and spindrift and offering few continuous fall lines. To most visitors, however, it is simply part of the view: a dark, triangular summit anchoring the skyline that appears on postcards and countless social media posts.

Top down view of descent line (Photo: Guillaume Pierrel)

After two nights in the cold and a long, human-powered exit back to the trailhead, the team left behind little evidence of their passage beyond a thin ribbon of ski tracks, soon erased by wind and snowfall.

It is important to understand what this story represents, and what it does not. The North Glacier of Mount Deltaform is not a backcountry ski objective in any recreational sense. It is a highly technical alpine route that demands expert-level climbing, glacial travel, rope management, and decision-making under constant objective hazard, including icefall and unprotectable exposure. Harrington, Lustenberger, and Pierrel are among a small group of athletes in the world with the experience and skill to operate in such terrain.

It is a reminder that even in the most familiar of places, there are still faces that wait decades for the right moment, and the right people, to be explored.

Reply