- Bow Valley Insider

- Posts

- A Bow Valley Author Aims to Reclaim the Lost History of Women in Mountaineering

A Bow Valley Author Aims to Reclaim the Lost History of Women in Mountaineering

A new book spotlights 20 climbers whose technical achievements and personal stories were long underrepresented in mountaineering literature

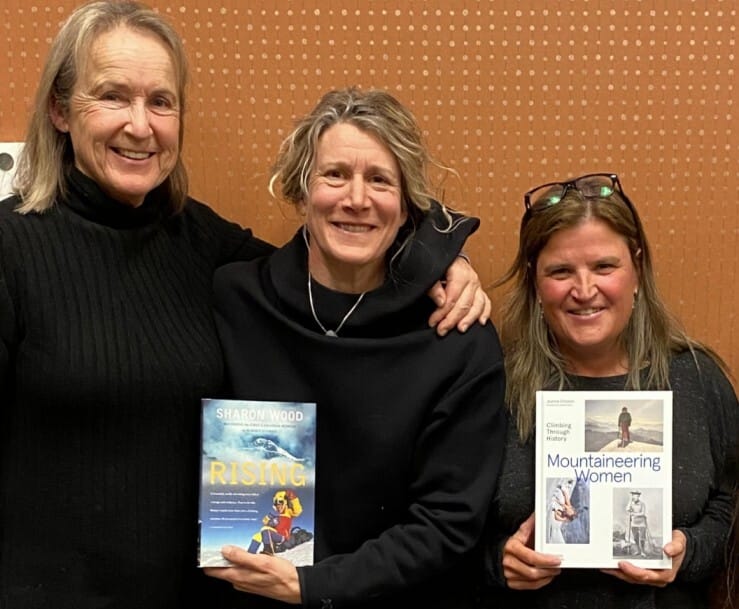

Left to right: Sharon Wood, Sarah Hueniken and author Joanna Croston during a Fireside Chat at the Canmore Public Library, where they discussed the making of The Mountaineering Women and the untold stories of women in climbing.

At a Jan. 13 Fireside Chat at the Canmore Public Library, author and Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Director Joanna Croston said her new book, The Mountaineering Women, was born out of a simple concern: too many foundational stories of women in the mountains have either never been told, or have faded from collective memory.

“This book is about the stories that have never been told about 20 really great women climbers,” Croston told the audience. “There’s this sort of legacy of women being maybe modest or a little more reluctant to share their stories. And so I kind of wanted to turn that around and put those out there in the world.”

Croston began the project with a personal list of roughly 80 women whose achievements she had encountered through years of work in mountain film, publishing, and festivals. That list, she said, was never originally intended to become a book.

“I’ve been collecting the names through my (day) job… I would add them and add them. It was never meant to be a book,” she said. “It was more just for me. I thought, ‘Oh, I’d like to learn more about this person.’”

When she brought the idea to her publisher, the scope narrowed.

“They were like, ‘That’s crazy. We’re not doing 80 women. It’s too much,’” Croston said. “So we chose 20.”

The final selection deliberately spans eras, continents, and levels of fame, from widely recognized figures such as Junko Tabei, the first woman to summit Everest, to climbers whose accomplishments had received little or no coverage.

“I wanted a mix,” Croston said. “Some of the stories are quite famous. Some of them you may never have heard of at all. I was really keen to include women like that too, as well as women from Asia, who we haven’t had tons of stories from.”

One of the climbers featured in the book, Sharon Wood, the first North American woman to summit Everest, said her own chapter avoids the climb for which she is most famous.

Sharon Wood, first North American woman to summit Everest

“I am really sick of the Everest story,” Wood told the audience. “There are other stories and good stories, and Joanna could see that.”

Instead, the book focuses on a lesser-known expedition in Peru, a climb Wood described as formative.

“It was a new route, super messy, super complicated, considered a death route,” she said. “I was kind of wondering if I was worthy enough. Am I really an alpinist? Do I really like this realm? And this climb told me that I loved alpine climbing.”

Croston said that choice was intentional.

“One thing I didn’t want to do was have an Everest book,” she said. “I wanted there to be alpinism in the book… stories of perseverance in the alpine environment.”

The event also highlighted how personal struggle, loss, and recovery often run alongside achievement in the mountains.

Sarah Hueniken, an ACMG mountain guide and one of the book’s featured climbers, described an attempt to link three major ice and mixed routes in the Ghost River Valley in a single day.

Sarah Hueniken, ACMG mountain guide

Mixed climbing refers to routes that combine ice, snow, and bare rock, requiring climbers to move between frozen features and technical rock sections using both ice tools and rock-climbing techniques.

Hueniken said the objective was not about setting a record, but about working through a period of grief following the death of a close partner in the mountains.

“I was coming back from a very difficult, completely life-changing, horrible experience,” Hueniken said. “I felt quite responsible for that, and very sad, and desperate. It was an extreme low in my life.”

The objective became a way to regain purpose and connection.

“I needed something to work toward,” she said. “I had to ask for help. I had to get my friends to help me on this journey because I couldn’t do it on my own… That was part of that healing journey.”

Croston said those themes of loss and resilience appeared repeatedly as she worked with the women in the book.

“I think tragedy and loss is pretty common in a mountaineer’s life,” she said. “In many ways, mountaineers and climbers have found a way to make it something that propels them forward again.”

Another thread that emerged during the discussion was how women’s accomplishments have historically been framed and judged differently. Croston pointed to the media reaction to British climber Alison Hargreaves, who was widely criticized after her death for taking risks as a mother.

“The press really dug into her when she died,” Croston said. “You wouldn’t say the same of a man in that situation. The narrative was, ‘She should never have been there.’”

Wood said this kind of framing reflects broader assumptions about how women in the mountains are expected to define success and legacy, with greater emphasis often placed on their roles as caregivers and partners than on their technical or athletic achievements. She noted that women climbers have not always been encouraged to see their accomplishments through the same lens of legacy, recognition and historical importance that has traditionally been applied to men.

For Croston, part of the urgency of the project was the realization that even some of the most influential women in climbing history are becoming unfamiliar to younger generations.

“Some young climbers don’t know who Catherine Destivelle is, which I find amazing,” Croston said, referring to the French alpinist widely regarded as one of the most influential and accomplished climbers of her generation. “We can’t lose those stories.”

Asked what she hopes the book will accomplish, Croston said the goal is less about advocacy than preservation and momentum.

“I just wanted to get the ball rolling,” she said. “I wanted people to be interested, and I want other people to write about this stuff. I wanted some of those stories not to be lost.”

Wood, who said she read the book in full despite initially opening it only to review her own chapter, said the result captured something broader than individual achievements.

“A lot of these women bust out of stereotypes,” Wood said. “People are feeling more liberated to be their weird, unusual, amazing, remarkable selves. And that’s what I liked about the book.”

Croston acknowledged that her original list of 80 names still exists, and that the question of a second volume remains open.

“I hope they would like to do another one,” she said. “We’ll see.”

For now, the conversation at the Canmore Public Library underscored a shift in how mountain history is being told: not as a catalogue of summits, but as a record of lives, struggles and contributions that had long remained in the background.

Reply