- Bow Valley Insider

- Posts

- “The Routes Are Just Gone”: How Melting Ice Is Changing the Rockies

“The Routes Are Just Gone”: How Melting Ice Is Changing the Rockies

Professional guides on what it means to work in terrain where ice once held the mountains together

Khaled El Gamal still hears his friend’s voice.

“Run. Run.”

They had been standing near Bow Glacier Falls on a warm June afternoon, taking photos at the base of a towering cliff. It was supposed to be a quiet stop on a first trip to the Canadian Rockies, a detour from Banff suggested by a stranger over breakfast. Then came a sharp crack, followed by a roar that sounded, witnesses later said, like an explosion.

“A huge portion of the mountain just fell,” El Gamal recalled in an interview with Bow Valley Insider. “It was rolling toward us. I froze. He yelled at me to run.”

A slab of rock the size of a multi-storey building sheared off the mountainside and thundered down the trail. El Gamal was struck, knocked to the ground, and buried in debris. His friend, who had urged him to flee, was killed. Another hiker, 70-year-old University of Alberta professor Jutta Hinrichs, also died.

On CBC Radio’s The Current on Jan. 14, host Matt Galloway played the audio of another witness, Elly Jackson, who described turning to see “the whole sheet of rock” breaking free and “exploding” down the slope. She ran, grabbing her dogs and her camera, barely outrunning the collapse.

Bow Glacier Falls before the rock slide event

For professional mountain guides, scenes like this are no longer unthinkable anomalies. They are becoming part of the landscape they work in.

In that same radio program, two guides, Mike Adolph, technical director of the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides, and Tim Ricci, director of operations for Yamnuska Mountain Adventures, described what it is like to work on glaciers that are rapidly shrinking and increasingly unstable. Both men spend much of their lives on the ice, guiding clients through terrain that is changing in ways they can see year to year, and sometimes week to week.

“As the ice is retreating, a lot of those hazards are being amplified,” Adolph said. “They’re more prominent. And it’s become a real concern for folks that are out there travelling and wanting to do so safely.”

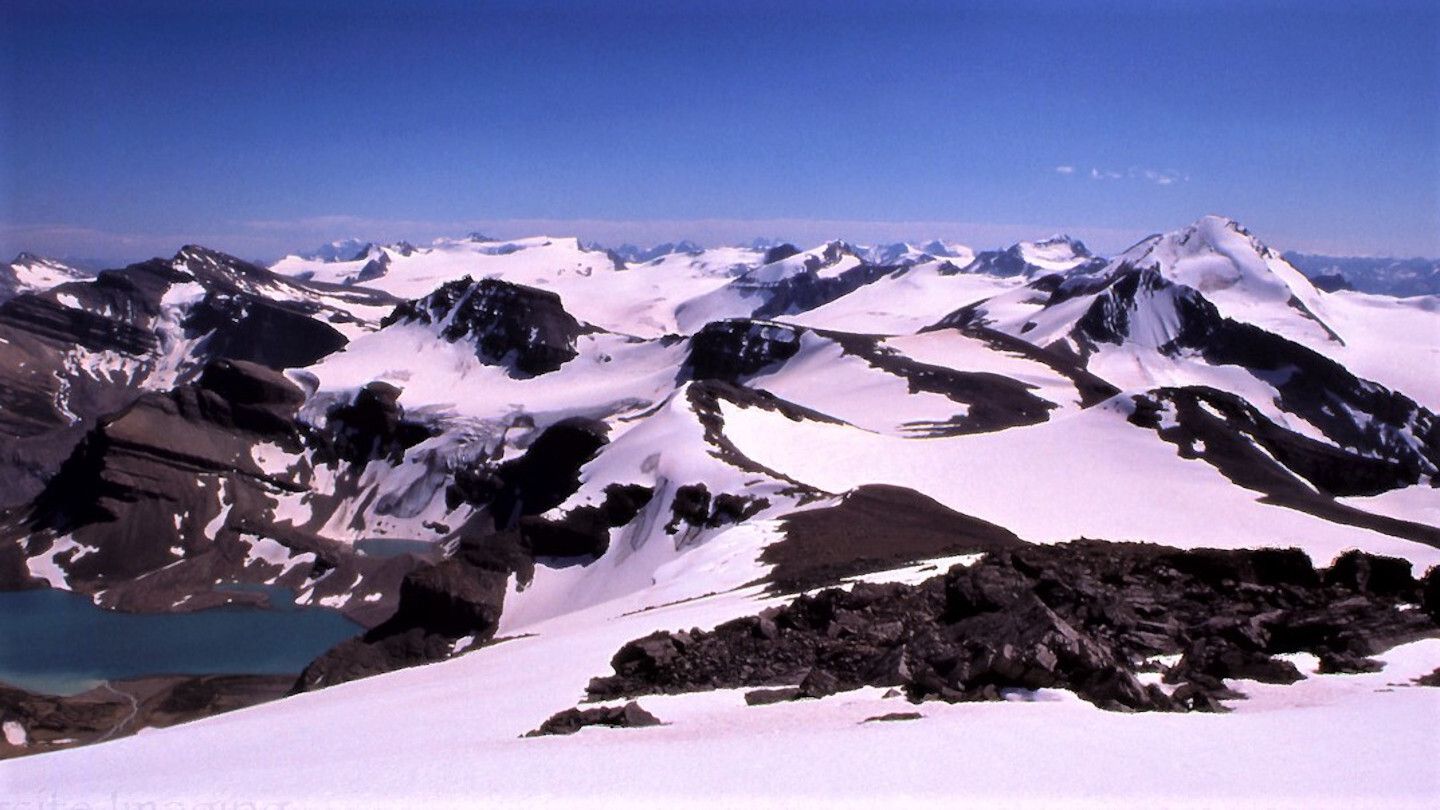

A Landscape in Rapid Retreat

Columbia Icefield, Canadian Rockies

Across western Canada, glaciers are shrinking at an accelerating pace. In British Columbia alone, there are more than 17,000 glaciers, and over the past 40 years they have lost nearly a quarter of their surface area. New research found that in 2025, western Canada lost an estimated 30 gigatons of glacier ice, enough to fill roughly 700 million hockey rinks.

That loss is not only altering the view. It is changing the structure of the mountains themselves.

Glacier ice once acted as a kind of glue, locking fractured rock in place and buttressing steep slopes. As it melts, loose faces are exposed, crevasses open, and slopes that were once frozen solid become increasingly unstable.

Routes That No Longer Exist

Ricci said entire travel routes used by climbers and skiers for decades have simply vanished.

“Where we would walk on ice, we’re now walking on loose rock and gravel,” he said. “Every season, we’re having to adapt and change how we travel to get to certain objectives, because in a lot of spots the glaciers are just gone.”

He described how familiar approaches to peaks must now be rerouted around newly formed lakes, unstable moraines, and collapsing ice features. The process, he said, feels like “reinventing the wheel almost every season.”

Mount Athabasca

Mount Athabasca, Canadian Rockies

One of the clearest examples is Mount Athabasca in the Columbia Icefield, long considered a classic training ground for glacier travel and a first summit for many aspiring alpinists.

“The Athabasca Glacier itself has melted back significantly,” Adolph said. “The folks that are doing the ice walks are now having to navigate a lake at the top of the glacier. The traditional routes are no longer viable.”

Areas once used to teach crevasse rescue and rope travel have disappeared altogether, or the remaining ice has become too unstable to stand on.

Temperature Whiplash

The physical retreat of glaciers is being compounded by increasingly erratic temperatures.

In January, Ricci noted, forecasts called for highs of 13°C in Canmore, a mid-winter warmth that would have been extraordinary only a few decades ago.

“We live in these peaks and valleys of very dramatic temperature swings,” he said. “That has a real impact on the frost and what happens out on the glaciers.”

Adolph described the cumulative effect of repeated freeze-thaw cycles, which can destabilize snowpacks and fracture rock.

“Nothing in the mountains really likes rapid change,” he said.

When the Safest Choice Is Not to Go

For guides whose livelihoods depend on moving through this terrain, the implications are profound.

Adolph recalled passing beneath a slope in the morning, only to return hours later to find a massive rockslide where they had walked. He has watched ice towers collapse from a distance and learned that the absence of warning is part of the new normal.

“There’s more uncertainty,” he said. “And oftentimes, it might mean that we just don’t go.”

Routes that were once climbable throughout the summer are now limited to narrower windows in late spring and early summer, when snow still binds loose rock and temperatures remain consistently below freezing. Even those windows, he said, appear to be shrinking.

Ricci acknowledged that the long-term future of guiding on glaciers is increasingly uncertain.

“The future of alpinism and operating on these glaciers is definitely at risk,” he said. “Not just for business, but for anybody wanting to recreate.”

Witnesses to Change

Wapta Icefield, Canadian Rockies

Neither guide framed the transformation in abstract scientific terms. Instead, they spoke as people who return year after year to the same slopes and see, in precise detail, what is missing.

Adolph remembered skiing onto the Wapta Icefield decades ago and looking out over kilometres of unbroken snow and ice.

“It’s an experience like you can’t really put to words,” he said. “You really just do need to be there.”

Ricci called glaciers “another planet,” a place of privilege and awe, and said that guiding now involves helping people understand not only the beauty of these places, but also their fragility.

A Fragile Future

For survivors like Khaled El Gamal, the implications are not theoretical. The mountains that drew him and his friend to Bow Lake became the site of an irreversible loss, one that geologists later said could not have been predicted.

On The Current, Galloway asked why the retreat of ice in remote ranges should matter to people who may never set foot on a glacier.

“These are the telltale signs,” Adolph replied. “We’re able to watch this firsthand. We’re seeing these changes year after year. We’re seeing it accelerate.”

Ricci added that taking people onto the ice, tying them into a rope, and letting them experience both the beauty and the instability of the terrain is one of the most powerful ways to make those changes real.

For those who work in the high places of the Canadian Rockies, the story of climate change is written directly into the ground beneath their feet.

Reply