- Bow Valley Insider

- Posts

- Fire Guards Around Canmore Could Pull Wildlife Out of Town, Biologists Say

Fire Guards Around Canmore Could Pull Wildlife Out of Town, Biologists Say

Biologists say the wildfire protection work is reviving long lost feeding grounds and may reduce growing conflict near town.

Debris from fire guard construction is burned near Canmore. The cleared areas will regenerate into food rich openings for wildlife.

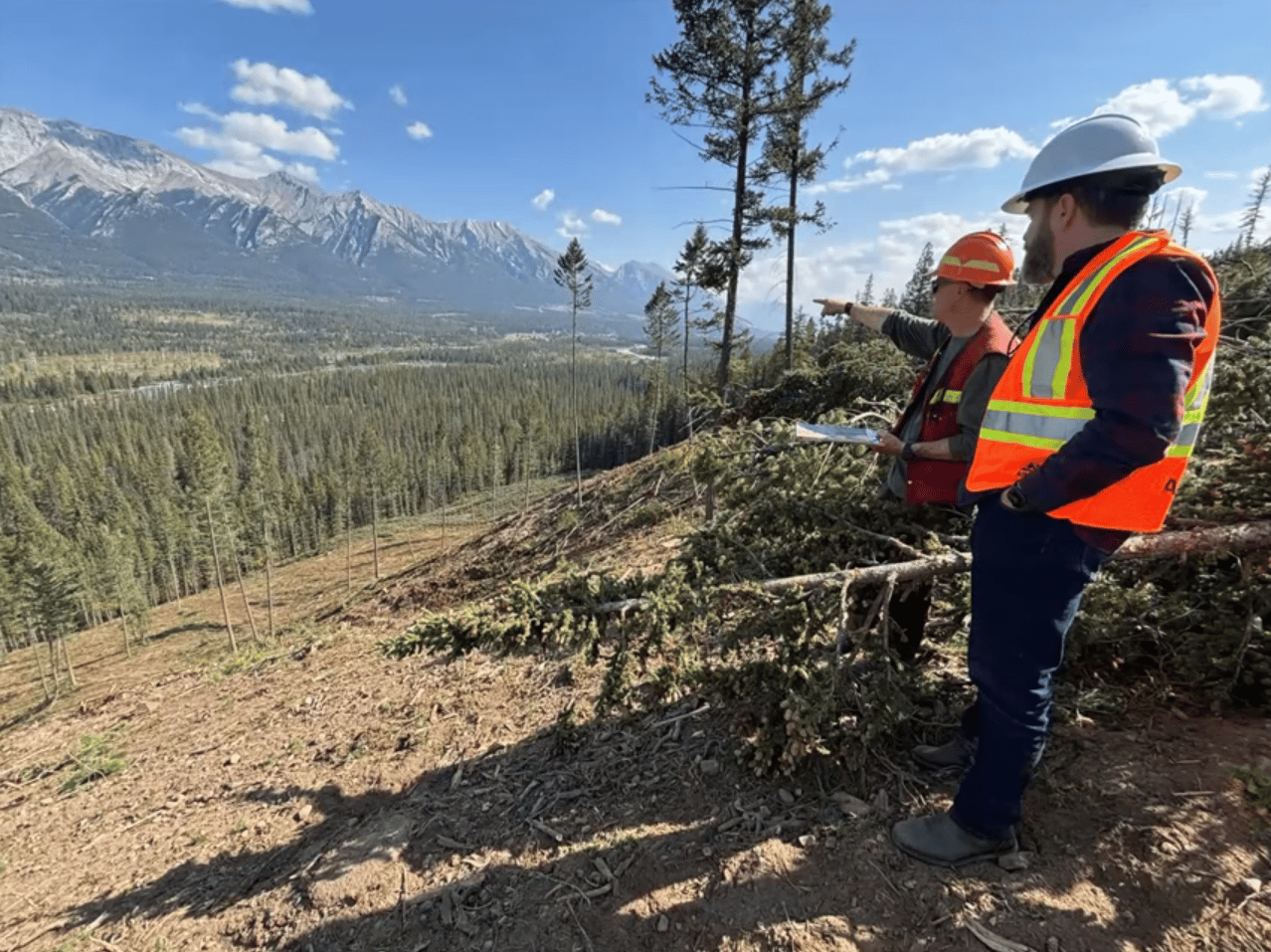

When most people look at the newly logged hillsides around Canmore, they see fire protection: wide-open strips of land, stacks of timber, and the unmistakable visual shock of forest suddenly removed. But to wildlife biologist John Paczkowski, Human Wildlife Coexistence Team Lead with Alberta Forestry and Parks, these clearings represent something else. They are the beginning of one of the valley’s most significant habitat restoration efforts in decades.

Paczkowski delivered that message on November 20 during an Earth Talks presentation hosted by the Biosphere Institute of the Bow Valley. His argument was straightforward. The Bow Valley’s long history of fire suppression has allowed forests to thicken, shade out food sources, and gradually erase the open, sunlit habitat that local wildlife once depended on.

“Over the last 120 years we have seen a loss of habitat right from the valley bottom to the top,” Paczkowski said. “The lack of sunlight getting to the forest floor means a lack of productivity for the foods that wildlife like to eat.”

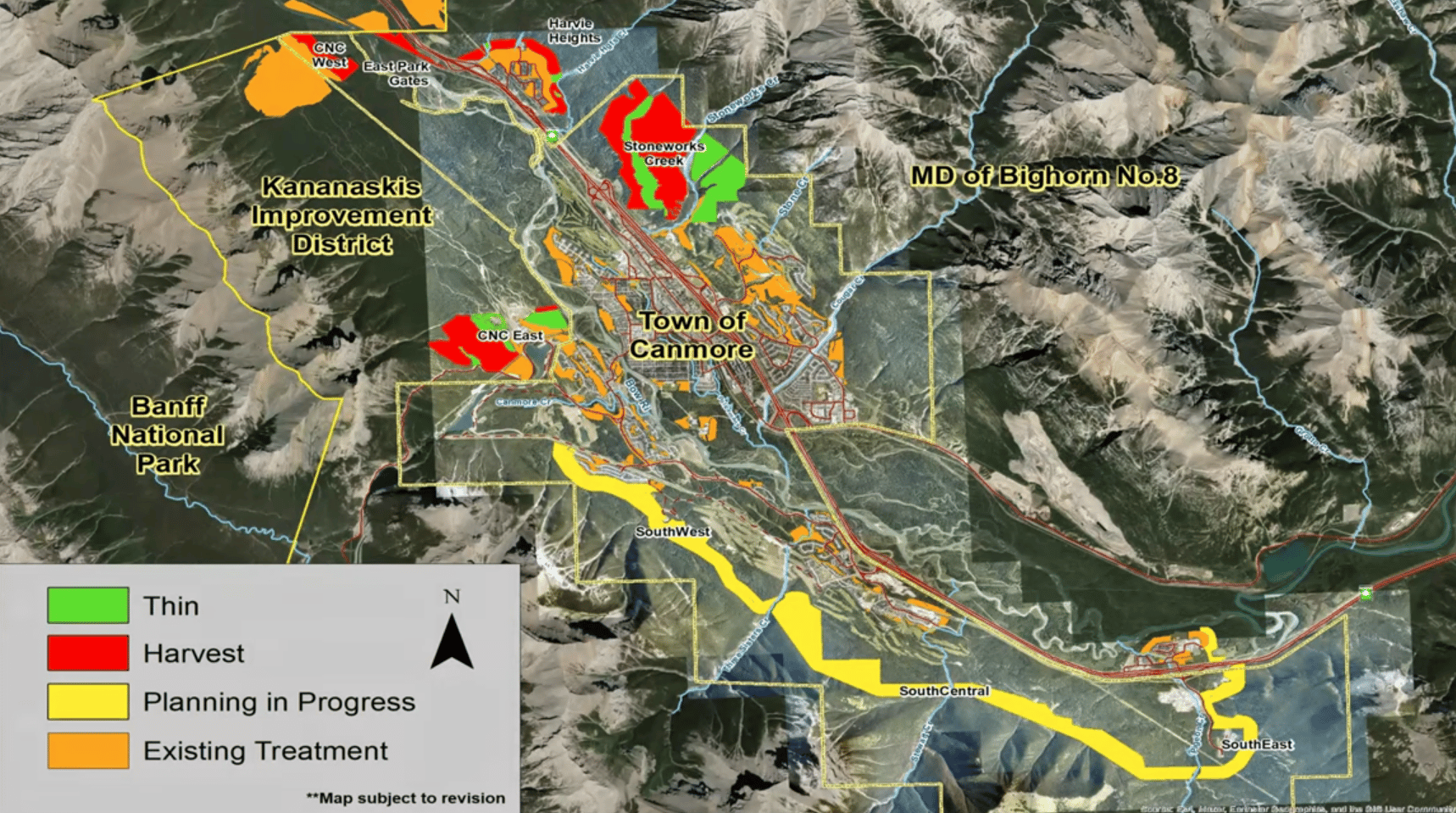

The current Bow Vally Fire Guard strategy

The new fire guards, built for community wildfire protection, are doubling as habitat openings that species such as elk and grizzly bears have shown strong preference for. In Paczkowski’s view, the logging work now unfolding around Canmore is not only protecting homes from fire, it is re-creating the mosaic of open spaces that once made the valley rich in wildlife.

“This opportunity to open up the forest a little bit creates understory growth that wildlife tend to like,” he explained, pointing to the berry filled openings near the Canmore Nordic Centre. “Grizzly bears are a species of open habitats. They like these open and edge habitats.”

This dual purpose was not widely understood before Wednesday’s presentation. Fire breaks are usually framed as a wildfire mitigation issue. Yet to Paczkowski, they are equally a habitat project, one he describes as personally meaningful after three decades working in the region.

“I am a bear researcher by training,” he said. “It has become near and dear to my heart to make these landscape level changes that will benefit wildlife.”

A landscape transformed by suppression

Paczkowski opened his presentation with historical photographs showing bare hillsides, sparse forest cover, and wide bands of grassland and shrubs circling the valley. Early Banff Park records describe frequent fires, many set intentionally by Indigenous peoples to maintain food sources and travel corridors.

The site of downtown canmore 120 years ago, showing sparse forest cover

Today the same views are dense green walls stretching from valley floor to ridge. That shift has consequences. In 2024, wildlife reports from Canmore show a heavy concentration of bear, elk, and cougar sightings inside town boundaries. Paczkowski believes habitat loss near town is a major driver.

“We are seeing more and more conflicts in and around the periphery of town and we are hoping to change that,” he said.

By re-creating open areas outside town, fire guards may help draw animals away from school grounds, roadsides, and residential neighborhoods. Early examples are promising. The Stoneworks Creek fire guard, completed last year, has already produced lush grasses, young aspen, and one of the healthiest berry patches in the valley, according to Paczkowski.

“That is my dream as a biologist,” he told the audience. “To see this area become a better area for ungulates and other critters.”

The science behind the openings

The presentation included compelling GPS data from one of the Bow Valley’s well-known grizzlies. The bear spent roughly 75% of its time inside cut blocks and forest openings, sometimes moving in a direct line between them. Paczkowski also showed tracking from Grizzly 148, whose movements through the Nordic Centre followed open meadow to open meadow, echoing decades of research on bear habitat selection.

A cut block near Canmore

To plan the new openings, Paczkowski relies on advanced mapping and terrain analysis to find areas that can support strong wildlife habitat. “I was trying to build ecological stepping stones so wildlife would move through the valley,” he said. “We want some patches to work up and out of the Nordic Centre.”

Four of those wildlife blocks above the Nordic Centre were completed earlier this month. They look raw today, with exposed soil and scattered retention patches. Paczkowski estimates they will take three to five years to begin functioning as high-quality habitat, and will hit their peak value between five and fifteen years.

Monitoring will rely heavily on a long-standing network of 120 wildlife cameras across the valley. “Some of those cameras have been up for 15 or 16 years,” he said. “We have a really nice baseline. We will have a snapshot over time before and after.”

Fire experts support the ecological benefits

Several panelists with decades of fire experience supported the ecological value of the new openings. Cliff White, a former Parks Canada fire management specialist with over forty years of experience, spoke to the historical mosaic of fire maintained landscapes.

“When you look down that landscape, every square foot of that was burned and looked after for berry crops and habitat,” White said. He described the valley’s current forest structure as far denser than natural conditions. “Even though we think we are burning a lot now, we are not even close to the large fire regimes.”

White warned that without ongoing disturbance, the valley risks accumulating dangerous levels of fuel. To him, the fire guards mimic historic patterns of burning and can help restore ecological balance.

The group also discussed smaller species. While some birds and small mammals prefer dark forests, Paczkowski noted that monitoring showed a “six or sevenfold increase” in open area bird species following similar habitat work. He acknowledged gaps in monitoring for small mammals and invited academic researchers to partner on more comprehensive studies.

The human reality: smoke, funding, and community adaptation

Panelists did not shy away from the challenges. The debris generated by the fire guards is immense. Many piles are so large that “a couple would fill this room,” Paczkowski said. Alternative disposal methods have been evaluated, including air curtain burners, mulching, burying, and biochar, but all were prohibitively expensive. As a result, smoke from pile burning will likely continue through winter.

“There will be more smoke,” he said, noting that the team is trying to minimize impacts by curing piles for a year and burning quickly in optimal weather conditions.

Funding remains a central concern. The work is supported by a provincial grant program, but the Bow Valley is also using revenue from harvested timber to reduce project costs. “There were hundreds of thousands of dollars coming back in to defer the cost,” Paczkowski said.

Despite the costs, many in the room emphasized that the valley is entering a period where active management is unavoidable. Growing towns, hotter summers, and fuel laden forests mean the Bow Valley must decide how to coexist with both wildlife and fire.

Bill Hunt, a longtime Parks Canada manager, framed the challenge as a cultural moment. “We have changed the attitudes of fire and thinning,” he said. “Now we need to rethink our attitudes around wildlife connectivity and corridors.”

A long-term vision for coexistence

Paczkowski closed his talk with a rare blend of optimism and urgency. Fire guards, he said, can protect communities and restore wildlife habitat at the same time when planned carefully. He recalled landscape level burns carried out decades ago that remain visible on the hillsides today, and hopes the current work will have similar staying power.

“It has been really exciting for a biologist to make these large landscape level changes that will benefit wildlife and hopefully keep people safe,” he said. “If we do this carefully and cautiously, we can come out with some real benefits for wildlife.”

For many residents, the fire guards still appear stark and unfamiliar. But for the valley’s biologists and fire experts, they represent a rare opportunity: a chance to reshape a forest that has grown beyond its natural limits, reduce conflict between people and wildlife, and create a landscape that is safer, more diverse, and more resilient than the one it replaces.

Reply