- Bow Valley Insider

- Posts

- Bow Valley Athletes Narrowly Miss Olympic Qualification as Ski Mountaineering Debuts

Bow Valley Athletes Narrowly Miss Olympic Qualification as Ski Mountaineering Debuts

Local national team athletes explain a little-known sport and how Olympic qualification came down to a single December race

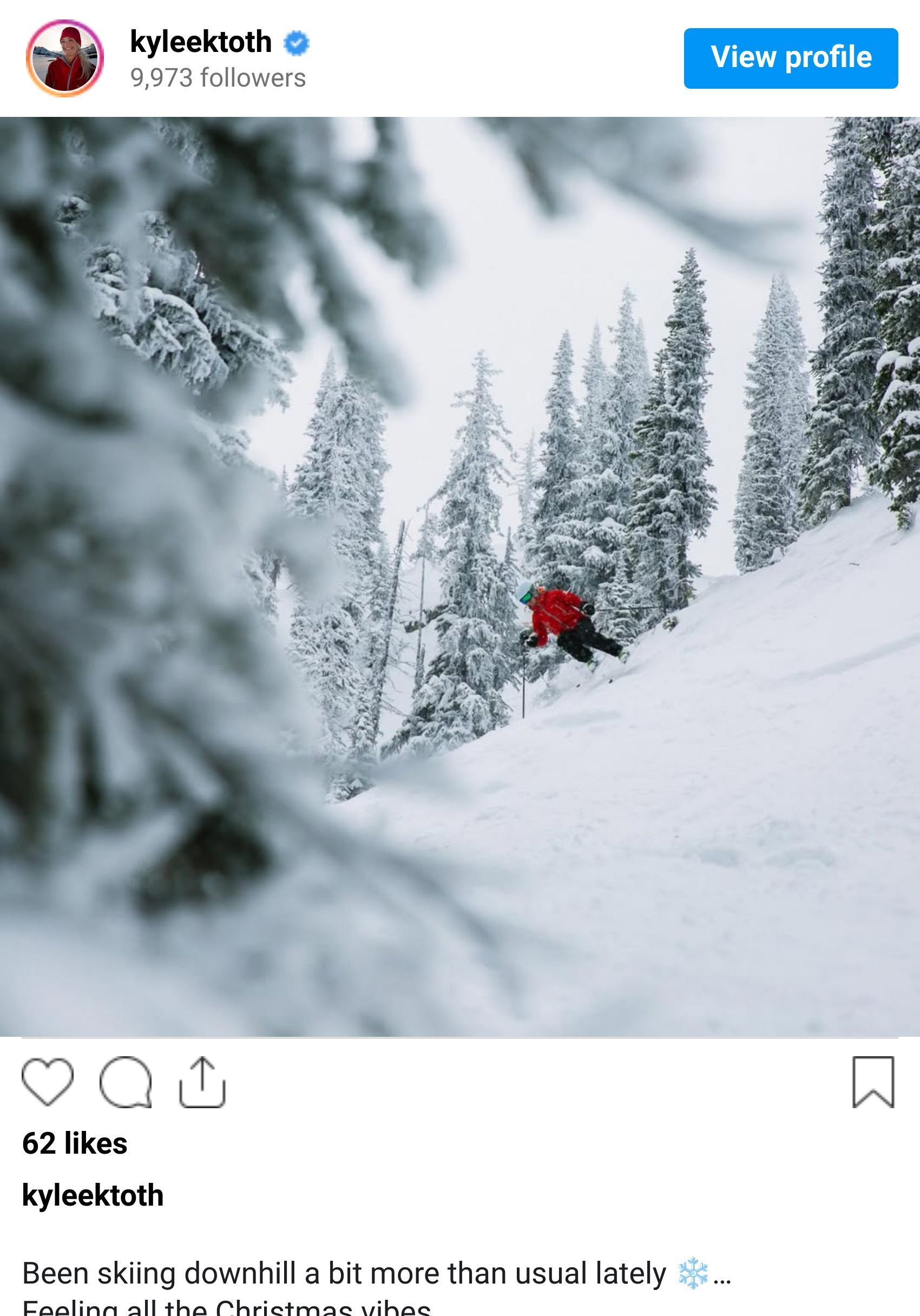

Kylee Toth, a Canadian national team ski mountaineering athlete, trains in the Bow Valley, where steep terrain and long climbs shaped Canada’s Olympic qualification campaign.

In 2026, ski mountaineering will appear on the Olympic stage for the first time.

The sport, often called skimo, blends uphill endurance, rapid-fire transitions, and technical downhill skiing into races that last anywhere from a few minutes to over forty. It has deep roots in the European Alps, a fast-growing World Cup circuit, and a small but intensely dedicated community in Canada.

This winter, that Olympic dream ran directly through the Bow Valley.

Local athletes spent months chasing qualification for Milano Cortina 2026, racing internationally to earn Canada a quota spot. When the final points were tallied, they finished just shy.

Disappointing, yes. But for the athletes involved, it was also a moment that revealed how close Canada came to standing on the start line of a brand-new Olympic sport.

“We were just shy of qualifying for the Olympics unfortunately,” said Emma Cook-Clarke, a Canadian national team member who lives and trains in Canmore. “Disappointed, yet proud of all of our efforts getting there.”

What Is Ski Mountaineering?

For most Canadians, ski mountaineering remains unfamiliar.

“Ski mountaineering, often called skimo, is a fast, endurance-based mountain sport where athletes race uphill and downhill on lightweight skis,” said Kylee Toth, another Canadian national team member. “Think of it as the winter equivalent of mountain running.”

Athletes climb using climbing skins attached to their skis, transition quickly at the top, and descend as fast as possible on ultralight equipment. Races link together multiple climbs, descents, and technical sections, forcing athletes to manage pacing, gear, and decision-making on the fly.

At the 2026 Olympics, only two events will be contested: the sprint and the mixed relay.

The sprint lasts about three minutes and includes skinning uphill, bootpacking with skis on the athlete’s pack, and a fast descent through gates. It is run in heats, similar to ski cross, where transitions and tactics matter as much as raw fitness.

The mixed relay lasts over forty minutes, pairing a woman and a man, each completing two short laps before tagging their partner. Mistakes are costly, and margins are tight.

A Bow Valley Training Ground

Canada’s skimo hopefuls did much of their preparation in and around Canmore, Banff, and the surrounding mountain corridors.

“The Bow Valley is a great place to train for ski mountaineering because the terrain, elevation, and access are all aligned with what the sport demands,” Toth said.

Athletes skin laps at ski areas, then drive to natural alpine terrain along Highway 93 North. Early-season snow and cold temperatures allow skiers to train on skis sooner than in most of North America, a key advantage for a sport that depends on time spent moving uphill on snow.

Cook-Clarke echoed that sentiment.

“The terrain is a perfect playground for training,” she said. “Very fortunate to be able to live and train here.”

Just as important is the community.

“The community we have is wonderful, full of supporters, friends, training partners, and professionals who can help in the process,” Cook-Clarke said.

A Narrow Olympic Pathway

Unlike most Olympic sports, ski mountaineering offers very few qualification spots.

Countries must first earn quota positions through results at World Cups, World Championships, and continental races. Only after a country secures a spot does its national federation select athletes.

For Canada, that meant a single race weekend carried enormous weight.

Olympic qualification ultimately came down to one World Cup weekend in early December, with results from the previous season also counting toward the final rankings. That event would determine whether Canada earned a spot for the sport’s Olympic debut.

The pressure was not just personal. Every result affected whether Canada would send any ski mountaineering athletes to the Olympics at all.

“Athletes are competing not only for personal results, but also to earn Canada the chance to have athletes on the start line in 2026,” Toth said.

When the final standings came in, Canada missed out.

The Work Behind the Scenes

Behind the short Olympic-format races is a year-round training load that rivals any endurance sport.

“Training right now is as specific as possible,” Cook-Clarke said. “Time on snow doing key workouts, transition practice, and time recovering.”

The sport demands aerobic capacity, downhill skill, technical efficiency, and mountain awareness, all performed at speed on skis that are far lighter than standard alpine gear.

“It’s full on,” Cook-Clarke said. “As with most high level sports, it requires sacrifice, endless hard work, time away and a large financial commitment.”

Toth was even more blunt about the physical demands.

“If you have ever ran straight up a hill you will know how hard that is,” she said. “The entire sport is uphill or downhill.”

Pride, Even Without a Spot

Missing Olympic qualification was difficult, but it did not erase what the athletes felt they accomplished.

“Qualifying isn’t just about competing,” Toth said. “It’s about representing a community, showing what’s possible in Canadian skimo, and honouring the athletes and coaches who paved the way.”

Cook-Clarke described the emotional mix more simply.

“Disappointed, yet proud of all of our efforts getting there,” she said.

Both athletes believe Olympic inclusion will still reshape the sport in Canada, even without Canadian representation in 2026.

“The Olympics have a magnetic effect on youth participation,” Toth said. “Once kids and teens see the sport on TV it will help to legitimize it as a viable option.”

Cook-Clarke hopes the momentum leads to something more lasting.

“I am excited to see the sport continue to grow in Canada, and for us to have the capacity to set up a development program,” she said.

A First Step, Not the Last

Ski mountaineering’s Olympic debut will be brief, fast, and unfamiliar to many viewers. For the Bow Valley athletes who chased it, the outcome was close, but not quite enough.

Still, they helped bring Canada within reach of a brand-new Olympic chapter.

And in a sport defined by climbing uphill, coming just short is often part of the path forward.

Reply