- Bow Valley Insider

- Posts

- Who Should Cover the Cost of Millions of Visitors in Canmore and Banff?

Who Should Cover the Cost of Millions of Visitors in Canmore and Banff?

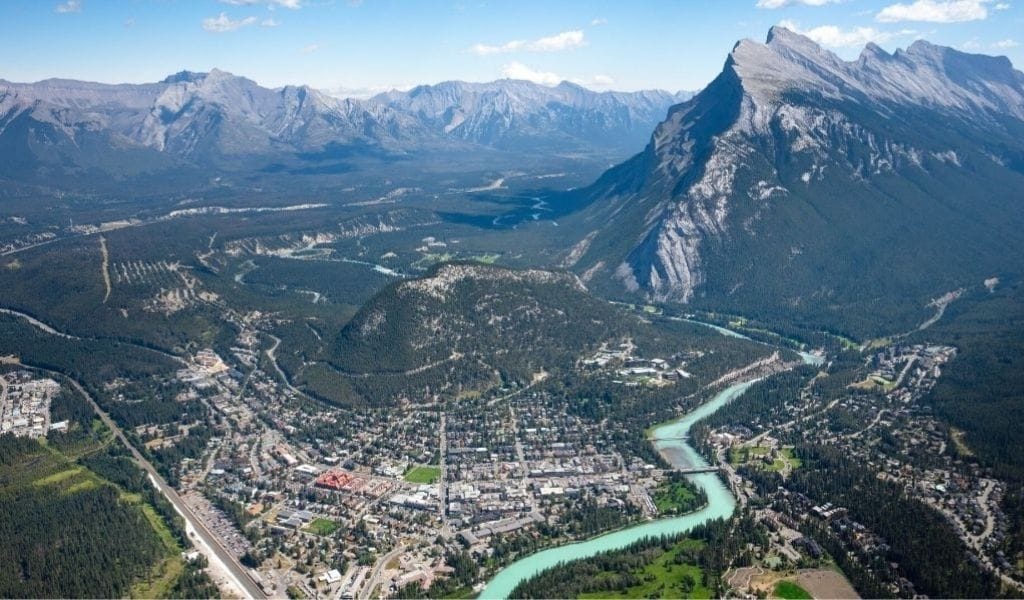

Canmore and Banff take different positions on a proposed "accommodation tax" as Alberta municipalities reconsider how to fund tourism.

From wastewater systems to trail networks, Canmore and Banff spend far more than most small towns to support the millions who visit each year. The idea that visitors should help pay for the services they use is gaining traction across Alberta, but in the Bow Valley, the two communities disagree on whether a proposed accommodation tax is the right way to get there.

The debate sharpened last week after Alberta’s municipalities voted at their annual convention to push the province for legislation that would allow towns to collect such a tax.

Both communities have long argued that local taxpayers shoulder the bulk of tourism-related costs. But this renewed call for provincial action has exposed a clear divide: for Canmore, the tax is a long-sought way to shift some costs to visitors; for Banff, it is far too narrow for a town that hosts millions but cannot grow its tax base.

The contrast underscores a central tension in Alberta’s mountain corridor. While the two towns face similar pressures, they are approaching this proposal from very different fiscal and legislative realities.

Canmore backs the tax: “Visitors should share the cost of the services they use”

Canmore Mayor Sean Krausert made no hesitation in supporting the accommodation tax resolution at the Alberta Municipalities convention. The reason, he says, is simple: tourism has grown faster than the town’s ability to fund the infrastructure that supports it.

“A tourism-based community builds infrastructure for the benefit of visitors that would not be needed by a similar sized community that has very few visitors,” Krausert said. “The costs of this extra infrastructure and services are largely borne by our local taxpayer.”

For Canmore, those costs show up everywhere. The town operates a wastewater treatment plant sized far beyond what a community of 15,000 residents would ordinarily need. Trails, roads, parks, garbage collection, utilities, parking systems, and recreation facilities all have to be built and maintained for a population that swells dramatically on weekends and holidays. In Krausert’s words, the list includes “housing for employees, sub-service infrastructure for water and wastewater, recreational amenities and parks, trails, traffic and road infrastructure, garbage collection, parking, and more.”

A municipal accommodation tax, he argues, would shift a portion of those costs back onto the people who generate them.

Under the model supported by Alberta Municipalities, and similar to the system used in Ontario, municipalities would have the authority to set their own tax rate and apply it to hotel stays and short-term rentals. Krausert noted that if Alberta adopted a legislative framework similar to Ontario’s, and if Canmore implemented a 2.5% rate, the town could collect roughly $11 million annually based on 2024 accommodation spending.

“That amount would be paid for directly by the visitor,” he said. “Not coming out of the businesses’ revenue.”

Krausert also pushed back against concerns that such a tax would make family travel more expensive. “These are normal charges often found on accommodation bills and are usually quite a small part of the overall bill,” he said. “No one would be punished by accommodation taxes.”

Though supportive, Canmore is cautious about projecting timelines. Alberta Municipalities has only just been given a mandate to advocate, and no formal request has yet gone to the province. “It is too early to know,” Krausert said. “A lot of things have to happen before a tourist accommodation tax becomes a reality.”

Banff looks for a broader fix: “We need recognition of our unique needs before choosing a tool”

The Town of Banff takes a different view. Mayor Corrie DiManno agrees that tourism is placing serious financial pressure on the town. She also agrees municipalities need better funding tools. But she does not believe an accommodation tax is the first answer.

The town’s position is also tied to what it sends back to the province. In 2019 alone (the last time this was studied), Banff contributed about $1.2 billion in GDP and $182 million in provincial taxes. DiManno says those contributions far exceed what the community receives in return, which is why she believes a municipal accommodation tax would be too narrow without a larger conversation about how tourism communities are funded.

“We would like a holistic discussion with the Province on the costs of tourism carried by municipalities,” DiManno said. “Municipalities are looking for a fair deal.”

Banff’s situation is not only shaped by its visitor load but by its legal structure. Unlike any other municipality in Alberta, Banff is governed by the federal National Parks Act, caps its commercial development, and cannot expand its land base beyond its roughly four square kilometres. It brings in millions of visitors but cannot physically grow hotel capacity or its tax base in response.

The result is a steadily widening fiscal gap. “Four million visitors in our four-square-kilometre town site each year has considerable impact on our roads, sidewalks, bridges, transit, sewers, policing, waste management, wildlife protection, and parks,” DiManno said.

And unlike Canmore, where overnight stays can still expand through new development and short-term rentals, Banff is largely at capacity. “Even with growth in visitors, we are at the limit of overnight stays,” she said. “Most of our growth pressures come from day visitation and tourism operations.”

Banff also emphasizes that the province already collects a 4% tourism levy on hotel stays. That money goes to the provincial treasury, not back into the communities where it was generated. At the same time, the town’s provincial funding allocations have declined or remained flat in recent years.

“We need recognition from the Province of our unique tourism benefits, and the unique impact on our small community from the millions of annual visitors,” DiManno said. “That is the starting point of discussions.”

Banff is also sensitive to the cumulative tax burden on its accommodation sector. Hotels in town already pay property taxes, corporate taxes, federal GST, and a longstanding 2% levy collected voluntarily by the industry to fund Banff and Lake Louise Tourism.

“In Banff, we do not think another tax on the hotel and B&B sector is the right answer,” DiManno said.

What the resolution actually calls for

The resolution passed at the Alberta Municipalities conference does not create a tax. Municipalities cannot start charging anything. Instead, the resolution directs Alberta Municipalities to advocate for a provincial legislative change.

According to the text of the resolution, Alberta Municipalities will ask the government to amend the Municipal Government Act to allow municipalities to establish a municipal accommodation tax through local bylaws. The province would set standards for transparency, accountability, and reporting. Municipalities would have authority to choose their rate, their collection method, and how the funds are allocated based on local needs.

The rationale is straightforward: Alberta municipalities have limited revenue tools. Property taxes pay for most local infrastructure, including tourism infrastructure. A municipal accommodation tax would tie visitor usage to visitor-funded infrastructure, reducing the load on residents.

Other provinces, including Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec, and Manitoba, already allow municipal accommodation taxes. These systems vary, but they generally share the principle that communities can levy a fee on overnight stays to support tourism-related expenses.

The Alberta government, however, has never created such a framework.

What has to happen next

There are several steps before any tax could exist in the Bow Valley.

Step 1: Alberta Municipalities prepares its advocacy

The organization now has a formal mandate to lobby the provincial government.

Step 2: The provincial government must amend legislation

Specifically, the Municipal Government Act must be changed to create an enabling framework.

Step 3: If the province agrees, it drafts and passes a bill

This could take months or years. There is currently no provincial timeline.

Step 4: Municipalities decide whether to adopt the tax

Even if the province creates a framework, it would be optional. Each municipality would have to hold discussions, consult the public, and pass a bylaw.

Step 5: Municipalities decide how to use the funds

The province could set parameters, especially around transparency and allocation. Towns would likely determine spending based on local infrastructure pressures.

Both mayors emphasized that, at this stage, everything is speculative. Alberta has not indicated whether it will take up the issue, and no legislative process has begun.

Two towns, one question: how should tourism be funded?

What the new resolution has surfaced is not a disagreement about whether tourism is expensive. Both communities acknowledge the financial strain that millions of annual visitors impose on small local tax bases. Both know the current system leaves municipalities paying for most tourism-related services while provincial tax revenue flows out of the Bow Valley.

The difference lies in the path forward.

Canmore wants the accommodation tax tool available as soon as possible. Banff wants the province to acknowledge its unique position and begin a broader conversation that includes industry, revenue-sharing, and recognition of the municipal costs associated with tourism.

Whether the province will move on either front remains unclear.

Reply